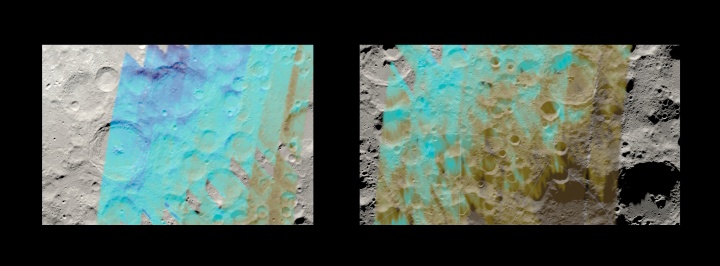

A new study based on data from the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) – a project by NASA and the German Space Agency (DLR) - has produced the first detailed, large-scale water map on the Moon near its south pole. It shows that the Moon's local geography plays an important role in the amount and distribution of water present: There is more water on the shaded sides of craters and mountains than on sunlit slopes or plains - a phenomenon we know from skiing.

"When we look at the water data, we can actually see crater rims and the individual mountains," said Bill Reach, director of the SOFIA Science Center at NASA's Ames Research Center in California's Silicon Valley and lead author of the study, which he presented at the 2023 Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. "We can even see differences between the sunny and shady sides of mountains thanks to higher water concentrations in shaded locations."

As early as 2020, researchers were able to use SOFIA data to provide long-hoped-for, unequivocal proof that molecular water also occurs in the warmer, sunlit lunar surface region, and not just at the shaded poles. Previous space missions to observe the lunar surface examined other wavelengths of light and could not distinguish water from molecules similar to hydroxyl.

"The new map of the Earth-facing side of the lunar surface extends from the 60th parallel to the south pole of the Moon," explains Bernhard Schulz, SOFIA Science Mission Operation Deputy Director at the University of Stuttgart, which is coordinating the SOFIA project on the German side. "With this data, we can see how water is distributed on the Moon at different positions of the sun, i.e. lunar diurnal times. That should tell us more about the origin of the observed water."

The Moon's water may exist in the soil as ice crystals or water molecules chemically bound to other materials. Where the Moon's water comes from - whether it is contained in the Moon's minerals or supplied solely by comets and solar wind - is still an open question. What is clear, however, is that the moon harbors much larger quantities of water than we previously thought.

Crucial resource for future missions

"Water is a crucial resource if humans want to explore the Moon in the long term or use it as a stepping stone for missions to Mars," explains Reinhold Ewald, a European astronaut and professor at the Institute of Space Systems (IRS) at the University of Stuttgart. "The more water we find already on the Moon, the easier it will be to implement these plans."

Additional observational data from other locations on the lunar surface are in the SOFIA archive and are currently being analyzed. "Thus, SOFIA will continue to make significant contributions to the occurrences and distributions of water on the lunar surface, despite the termination of its observing operations at the end of September 2022," Schulz said.

Links to the latest news:

- SOFIA Reveals Map of Moon’s Water Near Its South Pole, NASA News, March 15th, 2023

- SOFIA Finds More Water in the Moon’s Southern Hemisphere, NASA blog, August 26th, 2022

- Airborne Observatory SOFIA Discovers Molecular Water on the Moon, DSI News, October 26th, 2020

Further SOFIA Links:

- SOFIA Science Center

- NASA SOFIA Missions Page

- NASA SOFIA blog

- SOFIA Mission Page of DLR Space Agency (German)

- DLR SOFIA Projekt Page

- DLR Blogs for SOFIA (partly in German)

- DSI Image Galery (German)

- News Overview (partly in German)

- Project Chronicle (German)

SOFIA, the "Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy" is a joint project of the Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt e.V. (DLR; German Aerospace Center, grant: 50OK0901, 50OK1301, 50OK1701, 50OK1701 and 50OK2002) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). It is funded on behalf of DLR by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action based on legislation by the German Parliament, the State of Baden-Württemberg and the University of Stuttgart. SOFIA activities are coordinated on the German side by the German Space Agency at DLR and carried out by the German SOFIA Institute (DSI) at the University of Stuttgart, and on the U.S. side by NASA and the Universities Space Research Association (USRA). The development of the German instruments was funded by the Max Planck Society (MPG), the German Research Foundation (DFG) and DLR.